In the future, when people argue about whether a game can be a vessel for conveying themes or considered art, I hope Bioshock: Infinite will be part of the conversation. While in development for over 2 years, Bioshock: Infinite teased gamers with its unique art style and intense story through short gameplay clips and demos at various shows. Since its release, I’ve been converted into a believer and hope that Bioshock: Infinite acts as a sign for things to come in video games and how they can evolve.

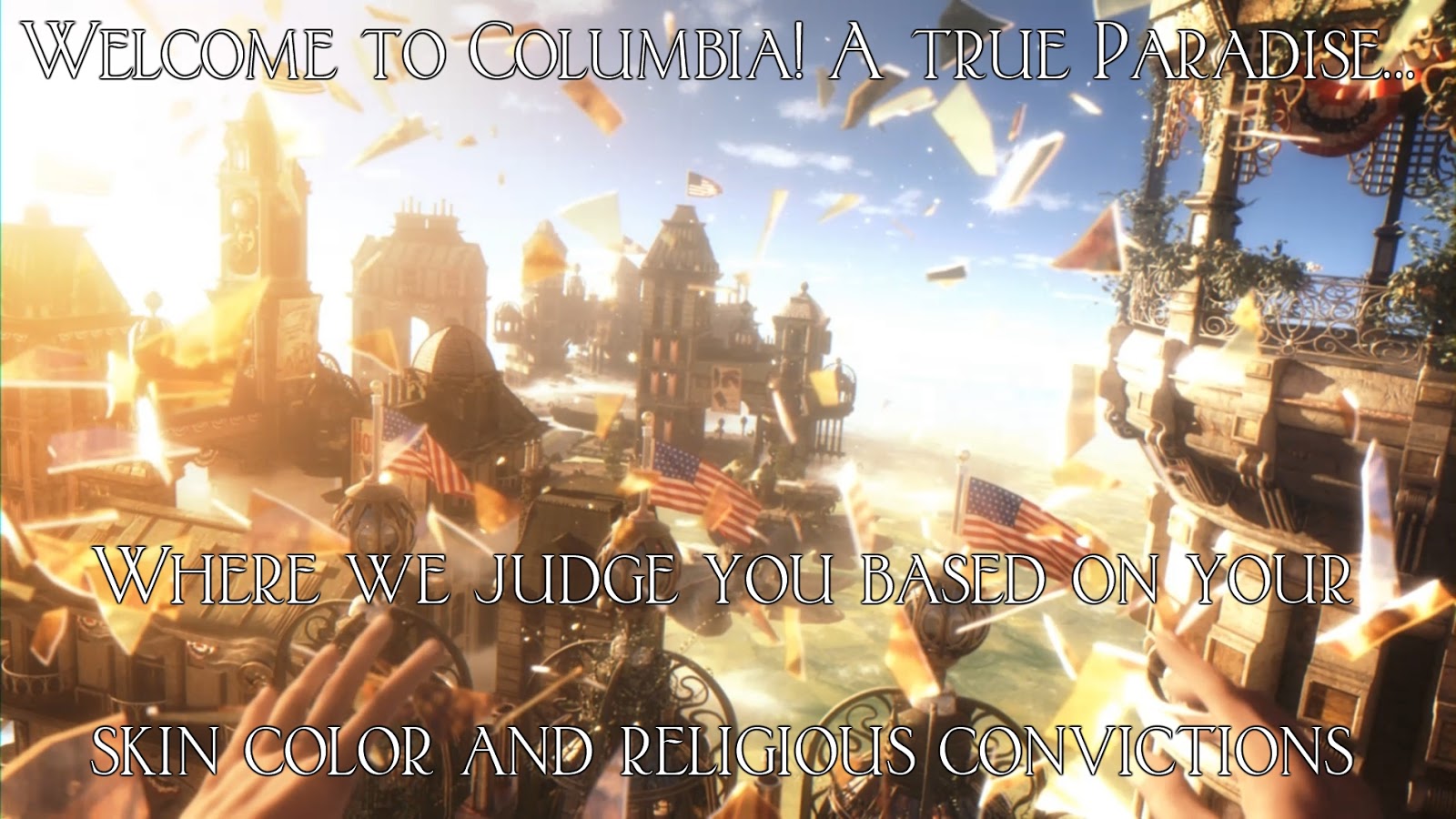

You experience this amazing tale through the eyes of Booker Dewitt, a man with many secrets, and apparently a large amount of debt that can be erased if she finds a girl, Elizabeth. After being shot up into the air and landing, you discover the flying city of Columbia, a place that seems equal parts nationalistic idealization of America, racial supremacy, and religious fervor. Everything about the world jumps out at you in a continuous flood of small details and quirks that drive the overall immersion in the world. From propaganda posters to brands made by in-game characters, and snippets of dialogue from the citizens, all serve to pull you deeper into the floating Eden. Columbia is a fantasy brought alive much like Rapture was in the first Bioshock, and just like its spiritual predecessor, it’s not without its ugly side. Being set firmly in the 1910s, civil rights was far from popular as is evident by the segregated washrooms, non-white vernaculars, and socioeconomic classification based on skin color. And as a large juxtaposition to Rapture, God plays very heavily into Columbia’s narrative. All over the city you can see people praying over the statues of Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington, the Americans they’ve deified to be Columbia’s moral pillars. Put all these together and Columbia represents the mindset of a more “pure” union, where the idea of white-supremacy is a religious truth, as is the faith in the founding fathers of the USA. Irrational Games has built a world that I want to explore over and over again and always see something new, from recordings found throughout the game to conversations with Elizabeth and other people in Columbia. These details serve to push forward Columbia’s narrative just as much as the story and social values.

You experience this amazing tale through the eyes of Booker Dewitt, a man with many secrets, and apparently a large amount of debt that can be erased if she finds a girl, Elizabeth. After being shot up into the air and landing, you discover the flying city of Columbia, a place that seems equal parts nationalistic idealization of America, racial supremacy, and religious fervor. Everything about the world jumps out at you in a continuous flood of small details and quirks that drive the overall immersion in the world. From propaganda posters to brands made by in-game characters, and snippets of dialogue from the citizens, all serve to pull you deeper into the floating Eden. Columbia is a fantasy brought alive much like Rapture was in the first Bioshock, and just like its spiritual predecessor, it’s not without its ugly side. Being set firmly in the 1910s, civil rights was far from popular as is evident by the segregated washrooms, non-white vernaculars, and socioeconomic classification based on skin color. And as a large juxtaposition to Rapture, God plays very heavily into Columbia’s narrative. All over the city you can see people praying over the statues of Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington, the Americans they’ve deified to be Columbia’s moral pillars. Put all these together and Columbia represents the mindset of a more “pure” union, where the idea of white-supremacy is a religious truth, as is the faith in the founding fathers of the USA. Irrational Games has built a world that I want to explore over and over again and always see something new, from recordings found throughout the game to conversations with Elizabeth and other people in Columbia. These details serve to push forward Columbia’s narrative just as much as the story and social values.

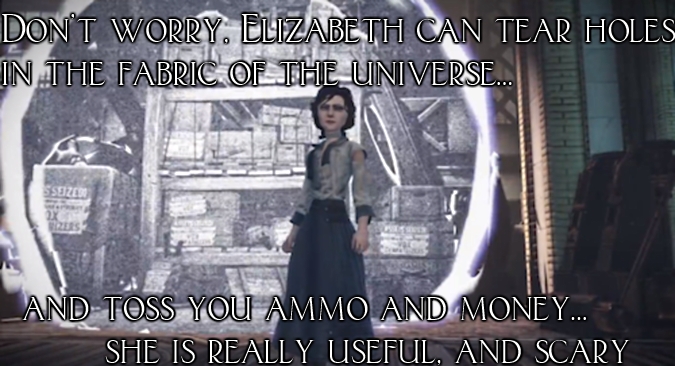

Without spoiling anything, I can explain that Booker is sent to find and take Elizabeth from Columbia. Most of the story is centered on the idea of getting the girl and getting out of dodge. As is typical of Irrational, the story takes some unexpected turns in the most beautiful ways possible, flexing their narrative muscle to remind us exactly why we love Bioshock so much. However, while the story itself is an amazing tale to experience, one of the most thrilling aspects of playing is interacting with Elizabeth. Acting as your companion for 90% of the game, she is a very important aspect in whether or not the game is a large boring escort mission, or an engaging experience with a very deep and satisfying partner. Elizabeth is most definitely the latter, as she is one of the most interesting companions that I have had in a game. If anything, you’re the one she’s on an escort mission with. She doesn’t simply tag along while you run around and kill people. Booker interacts with her; she has dialogue and internal conflicts as Columbia shows her a very harsh reality that is a stark contrast to the metaphorical and literal birdcage that she grew up in. She is even central to some of the decisions you make in game. While they don’t have much of a larger impact on how the game is played, Irrational could have simply said “go here to further the story, or there is another place for side missions.” Instead, Elizabeth acted as a conduit for exploration, wanting to see everything Columbia had to offer. Her personal growth affects that of Booker as well, the two of them teaching one another through their shared experiences. This narrative element is especially powerful since Booker represents selfish pessimism, wanting to kidnap Elizabeth and get out so he can have his debt repaid, and Elizabeth represents the naïve innocence that comes with having little life experience. As the two cut their way across the flying city, their experiences change them almost as much as their conversations. One of the things that surprised me about Bioshock: Infinite, was how it dealt with areas of discussion, like religion and racism, with tact and elegance through the conversations of two radically different people with a reasonably similar goal.

Without spoiling anything, I can explain that Booker is sent to find and take Elizabeth from Columbia. Most of the story is centered on the idea of getting the girl and getting out of dodge. As is typical of Irrational, the story takes some unexpected turns in the most beautiful ways possible, flexing their narrative muscle to remind us exactly why we love Bioshock so much. However, while the story itself is an amazing tale to experience, one of the most thrilling aspects of playing is interacting with Elizabeth. Acting as your companion for 90% of the game, she is a very important aspect in whether or not the game is a large boring escort mission, or an engaging experience with a very deep and satisfying partner. Elizabeth is most definitely the latter, as she is one of the most interesting companions that I have had in a game. If anything, you’re the one she’s on an escort mission with. She doesn’t simply tag along while you run around and kill people. Booker interacts with her; she has dialogue and internal conflicts as Columbia shows her a very harsh reality that is a stark contrast to the metaphorical and literal birdcage that she grew up in. She is even central to some of the decisions you make in game. While they don’t have much of a larger impact on how the game is played, Irrational could have simply said “go here to further the story, or there is another place for side missions.” Instead, Elizabeth acted as a conduit for exploration, wanting to see everything Columbia had to offer. Her personal growth affects that of Booker as well, the two of them teaching one another through their shared experiences. This narrative element is especially powerful since Booker represents selfish pessimism, wanting to kidnap Elizabeth and get out so he can have his debt repaid, and Elizabeth represents the naïve innocence that comes with having little life experience. As the two cut their way across the flying city, their experiences change them almost as much as their conversations. One of the things that surprised me about Bioshock: Infinite, was how it dealt with areas of discussion, like religion and racism, with tact and elegance through the conversations of two radically different people with a reasonably similar goal.

Irrational Games has set the bar for understanding how to deal with delicate issues in video games. While they used some creative license to establish the fiction of the universe, the religious, racist, and historical elements all serve as a way to establish the world that you are in, and convey a powerful theme that has nothing to do with these issues. All of the emotional introspection that comes from the characters has to do with personal convictions and fears, and nothing to do with any controversial topic that was the vessel for the message meant for the player. This game is absolutely brilliant at emphasizing the player’s empathy with the characters while striking a balance with the social issues of the game. Never does the story of Booker and Elizabeth take a backseat to the social issues of Columbia. That’s not to say the quandaries presented in this game are downplayed, but rather that they integrate seamlessly with the story of the main characters. Instead of displaying some kind of fantasy America and saying “Look at how bad these people are,” Bioshock: Infinite uses antagonists like Father Comstock as a tool for encouraging a change in perspective and personal reflection, and uses them well. I have never felt so emotionally conflicted while playing a game like this before, and maybe that is in part because game developers have never dared to deal with issues like this in a serious and elegant manner. A common idea I have been hearing lately is that video games are akin to the first black-and-white movies in the 40’s, used only as simple entertainment without dealing with larger issues. I think Bioshock: Infinite should serve as proof that not only can video games deal with bigger issues than shooting the next one hundred people, but that they are evolving to do so while retaining their entertainment value.

Irrational Games has set the bar for understanding how to deal with delicate issues in video games. While they used some creative license to establish the fiction of the universe, the religious, racist, and historical elements all serve as a way to establish the world that you are in, and convey a powerful theme that has nothing to do with these issues. All of the emotional introspection that comes from the characters has to do with personal convictions and fears, and nothing to do with any controversial topic that was the vessel for the message meant for the player. This game is absolutely brilliant at emphasizing the player’s empathy with the characters while striking a balance with the social issues of the game. Never does the story of Booker and Elizabeth take a backseat to the social issues of Columbia. That’s not to say the quandaries presented in this game are downplayed, but rather that they integrate seamlessly with the story of the main characters. Instead of displaying some kind of fantasy America and saying “Look at how bad these people are,” Bioshock: Infinite uses antagonists like Father Comstock as a tool for encouraging a change in perspective and personal reflection, and uses them well. I have never felt so emotionally conflicted while playing a game like this before, and maybe that is in part because game developers have never dared to deal with issues like this in a serious and elegant manner. A common idea I have been hearing lately is that video games are akin to the first black-and-white movies in the 40’s, used only as simple entertainment without dealing with larger issues. I think Bioshock: Infinite should serve as proof that not only can video games deal with bigger issues than shooting the next one hundred people, but that they are evolving to do so while retaining their entertainment value.

Since Bioshock: Infinite is a first person shooter, the combat is very fast-paced and frantic as you run around various areas and fight your way through multiple types of enemies. Using a combination of weapons found around Columbia and Vigors, special powers from tonics found in certain areas, Booker Dewitt has to fight many battles to make his way through the city. Branded as the “False Shepard” in the beginning of the game and the public opinion of you quickly turns from non-existant to one of hate and fear, meaning you are forced to fight for every inch to get to Elizabeth and to get her out of the city. The weapons are varied and interesting as you start out with basic weapons like shotguns or carbines, and throughout the game find unique twists on the basic designs. Guns like the Repeater, a faction-specific modification of the standard machine gun, and Heater, a sort of fire shotgun, keep the gameplay fresh by giving you more options on how to deal with each new enemy and confrontation. The Vigors in the game, not unlike the Plasmids in the first Bioshock, are what really keep the battles exciting and interesting. Varying from your standard electric bolt to pushing people away or drawing them in with a jet of water, the vigors are powerful effects that really allow you to handle a multitude of situations. The only real downside is that since you can have only two Vigors and two weapons equipped at any one time, you have to be careful about mis-equipping yourself and not having the ideal tools to deal with a situation. With Vigors, it’s not as bad since you can just re-adjust on the fly from a menu, but with the guns in the game you can only have two, period. And it can really be unfortunate if you have a revolver and a machine gun if you find yourself battling against a Handyman or Motorized Patriot.

Since Bioshock: Infinite is a first person shooter, the combat is very fast-paced and frantic as you run around various areas and fight your way through multiple types of enemies. Using a combination of weapons found around Columbia and Vigors, special powers from tonics found in certain areas, Booker Dewitt has to fight many battles to make his way through the city. Branded as the “False Shepard” in the beginning of the game and the public opinion of you quickly turns from non-existant to one of hate and fear, meaning you are forced to fight for every inch to get to Elizabeth and to get her out of the city. The weapons are varied and interesting as you start out with basic weapons like shotguns or carbines, and throughout the game find unique twists on the basic designs. Guns like the Repeater, a faction-specific modification of the standard machine gun, and Heater, a sort of fire shotgun, keep the gameplay fresh by giving you more options on how to deal with each new enemy and confrontation. The Vigors in the game, not unlike the Plasmids in the first Bioshock, are what really keep the battles exciting and interesting. Varying from your standard electric bolt to pushing people away or drawing them in with a jet of water, the vigors are powerful effects that really allow you to handle a multitude of situations. The only real downside is that since you can have only two Vigors and two weapons equipped at any one time, you have to be careful about mis-equipping yourself and not having the ideal tools to deal with a situation. With Vigors, it’s not as bad since you can just re-adjust on the fly from a menu, but with the guns in the game you can only have two, period. And it can really be unfortunate if you have a revolver and a machine gun if you find yourself battling against a Handyman or Motorized Patriot.

The various enemies and use of the skyhook system really keep the long firefights in the game appealing. In the beginning of the game you find a Skyhook, which gives you access to rails set up throughout Columbia. With the skyrails, verticality is added to combat, adding an extra dimension to combat. Riding on the lines lets you ride around and attack from multiple angles while shooting at your enemies from afar, or running away when the heat is on. That combined with Elizabeth’s ability to pull things from other universes, shooting people in the face has never felt so gratifying. Elizabeth has a very unique ability to pull things in from other universes, a useful ability when you need to fight off opponents. Occasionally she can pull through a hook to jump on to, but it gets even better when you can instantly give you cover or a gun turret to help you in the fight. And when you fight with big tanks like the Handymen or the armored Pyro enemies, you’ll need all the help you can get. Thankfully while Elizabeth is a metaphorical princess that you save from her tower, she is literally a lifesaver when you fight your way through Columbia. Not only is she the one that brings you back from the dead, but she can toss you resources like ammo, health, or money at random moments in the game. The money sounds less important than ammo or health, but it really comes in handy when trying to upgrade your weapons and Vigors.

The various enemies and use of the skyhook system really keep the long firefights in the game appealing. In the beginning of the game you find a Skyhook, which gives you access to rails set up throughout Columbia. With the skyrails, verticality is added to combat, adding an extra dimension to combat. Riding on the lines lets you ride around and attack from multiple angles while shooting at your enemies from afar, or running away when the heat is on. That combined with Elizabeth’s ability to pull things from other universes, shooting people in the face has never felt so gratifying. Elizabeth has a very unique ability to pull things in from other universes, a useful ability when you need to fight off opponents. Occasionally she can pull through a hook to jump on to, but it gets even better when you can instantly give you cover or a gun turret to help you in the fight. And when you fight with big tanks like the Handymen or the armored Pyro enemies, you’ll need all the help you can get. Thankfully while Elizabeth is a metaphorical princess that you save from her tower, she is literally a lifesaver when you fight your way through Columbia. Not only is she the one that brings you back from the dead, but she can toss you resources like ammo, health, or money at random moments in the game. The money sounds less important than ammo or health, but it really comes in handy when trying to upgrade your weapons and Vigors.

Throughout Columbia, vending machines are set up to let you purchase ammo, health, and upgrades. A fun nod to the vending machines in the first Bioshock, the machines are often passed up since many of the upgrades and improvements cost a hefty amount of silver eagles, the chosen currency in Columbia. Thanks to the help of Elizabeth, a lot of the upgrades are affordable and useful, like an increase in damage on your shotgun or a more powerful shock from your Shock Jockey Vigor. While the combat is entertaining and peppered with unique twists that keep interesting, it can turn into a hide-and-shoot gallery, and it’s moments like that when you can thank Elizabeth for finding money instead of health. The challenging fights quickly became exhausting experiences, but in the best possible way. Fighting my way through hordes of non-trivial enemies to advance the story added a certain amount of desperation to the situation, knowing what I had to do just to get Elizabeth out of the city, and for me it made the game all the better.

Throughout Columbia, vending machines are set up to let you purchase ammo, health, and upgrades. A fun nod to the vending machines in the first Bioshock, the machines are often passed up since many of the upgrades and improvements cost a hefty amount of silver eagles, the chosen currency in Columbia. Thanks to the help of Elizabeth, a lot of the upgrades are affordable and useful, like an increase in damage on your shotgun or a more powerful shock from your Shock Jockey Vigor. While the combat is entertaining and peppered with unique twists that keep interesting, it can turn into a hide-and-shoot gallery, and it’s moments like that when you can thank Elizabeth for finding money instead of health. The challenging fights quickly became exhausting experiences, but in the best possible way. Fighting my way through hordes of non-trivial enemies to advance the story added a certain amount of desperation to the situation, knowing what I had to do just to get Elizabeth out of the city, and for me it made the game all the better.

Bioshock: Infinite will easily be defined as a classic game years later; it’s certainly one of the best games I’ve ever played. At this point I would usually recommend this game if you’ve played others like it, but that doesn’t do the game enough justice. This game is just too good to limit the audience — everyone should play it. This 8-10 hour experience offers an impossibly deep story, challenging gameplay, and more immersion than I’ve seen in some time. Bioshock: Infinite is not only a phenomenal game, but it’s a truly outstanding piece of media. From the aesthetics to the mechanics and everything in-between, this is a game that stands away from the pack on the cutting edge of what games can truly be.

Great article! I thought the game was stunning.

I do wish more tears that showed other time periods and interactive elements were featured throughout such as the horse incident and that Elizabeth in opening them could assist in battle a bit more actively than just summoning objects, like literally have a bus actually breaking through and hitting people and then vanishing on the other side, or her blipping people away etc. A slightly bit more active role in combat aside from throwing you things and bringing in cranes and carts and turrets and tanks etc would have been great. Also more choices in helping people or otherwise. Other than that her AI was pretty awesome.

I do have one correction, but it’s a big one only because I’m a cinephile.

To say that early films were purely entertainment is a bit erroneous. The first black and white movies with narrative structure we’d call a feature film also started in the 1910’s.and 20s not the 1940s (For reference Hollywood in 1939 produced perhaps the longest list of now classic films now considered pillars in American film history; films had matured by the 1940s.)

The first deemed “modern” full length feature film was W.D. Griffith’s The Birth of A Nation from 1915 which was an incredibly racist epic chronicling the start of the KKK.. It’s mentality very much falls in line with the jingoism, white supremacy of the era and of the world of Columbia and the propaganda presented there by Comstock. It exemplifies it really.

You are right that videogames are still for the most part care for very narrative driven Japanese RPGs are pretty fluffy and even those can be pretty standard and unsophisticated. Storylines are getting more sophisticated here and there but things would be a lot different if every game approached the story and its motifs and purpose the way they do with the Bioshock games.

The game’s criticism of American jingoism, our ugly racist and bloody history, the slaughter of Native Americans, the Boxer rebellion and I think its blatant criticism of radical Mormonism and fervent Christianity overall was very, very, ballsy and amazing to see in a videogame. We cannot forget these things I hope people a disturbed by it. More games need as you suggest interject these kind of criticisms, motifs and sophistication in their games.

Sorry if that’s long, again great job! If Bioshock is setting the bar I’m excited to see what other games in response will try to do.

I get a little sick of religion-slamming, but the game is absolutely beautiful. Fantastic artwork, and I want to make costumes and props based nearly all of it. Well done review!