This week Gen Con LLC (the company that runs Gen Con) sent an open letter to Indiana Governor Mike Pence threatening to look for a new state to host their conventions, due to the passing of SB 101 through the Indiana state legislature. SB 101, which is making the rounds in the media affectionately referred to as a “religious freedoms” bill, could offer protection to Indiana business owners to deny service to same-sex couples. The bill is entitled “Religious Freedom Restoration,” and the Governor plans on signing into law on Monday has been signed into law as of this morning in a private ceremony at his statehouse office, according to IndyStar.

Gen Con LLC owner Adrian Swartout sent an open letter to the Governor regarding SB 101 over Twitter this past Tuesday, asking him to withdraw his support for the bill (which apparently had no effect on the Governor’s decision).

Gen Con LLC owner Adrian Swartout sent an open letter to the Governor regarding SB 101 over Twitter this past Tuesday, asking him to withdraw his support for the bill (which apparently had no effect on the Governor’s decision).

In his letter he stated, “Legislation that could allow for refusal of service or discrimination against our attendees will have a direct negative impact on the state’s economy, and will factor into our decision-making on hosting the convention in the stats of Indiana in future years.” He closed with a simple request – “We ask that you please reconsider your support of SB 101.”

Swartout seemingly saw that the only way to be heard wasn’t to appeal to a sense of human decency, but instead to fire a warning shot at their bank accounts. Sadly, in some matters, usually political, that can count for way more. Take a look at his full letter here.

Pence used Notre Dame University as an example for this law, namely their taking issue with a part of the Affordable Care Act that requires insurance coverage for contraceptives.

In his news conference this morning, he stated, “Today I signed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, because I support the freedom of religion for every Hoosier of every faith,” he said in a statement. “The Constitution of the United States and the Indiana Constitution both provide strong recognition of the freedom of religion but today, many people of faith feel their religious liberty is under attack by government action.”

In his news conference this morning, he stated, “Today I signed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, because I support the freedom of religion for every Hoosier of every faith,” he said in a statement. “The Constitution of the United States and the Indiana Constitution both provide strong recognition of the freedom of religion but today, many people of faith feel their religious liberty is under attack by government action.”

Local companies like Salesforce, and even Republican Mayor Greg Ballard of Indianapolis spoke out against the bill. “I had hoped the Statehouse wouldn’t move in this direction on RFRA,” Mayor Ballard said. “but it seems as if the bill was a fait accompli from the beginning. I don’t believe this legislation truly represents our state or our capital city. Indianapolis strives to be a welcoming place that attracts businesses, conventions, visitors and residents. We are a diverse city, and I want everyone who visits and lives in Indy to feel comfortable here. RFRA sends the wrong signal.

In response to criticism that it could in fact lay a groundwork for discrimination, Pence had the following to say:

“This bill is not about discrimination, and if I thought it legalized discrimination in any way in Indiana, I would have vetoed it. In fact, it does not even apply to disputes between private parties unless government action is involved. For more than twenty years, the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act has never undermined our nation’s anti-discrimination laws, and it will not in Indiana.”

So that being said, I don’t understand the motivation for this bill. If both the United States Constitution and the Indiana State Constitution both provide “strong recognition of the freedom of religion,” and that the federal version of the law never undermined any anti-discrimination laws, then why was this bill even needed? I’m reminded of the last scene in A Few Good Men, when Colonel Jessup was being questioned:

Kaffee: That’s not what you said. You said he was being transferred, because he was in grave danger.

Jessup: That’s correct.

Kaffee: You said he was in danger. I said “grave danger”? You said…

Jessup: I recall what I said.

Kaffee: I could have the court reporter read back to you…

Jessup: I know what I said! I don’t have to have it read back to me, like I’m…

Kaffee: Then why the two orders? Colonel?

Jessup: Sometimes men take matters into their own hands.

Kaffee: No, sir. You made it clear just a moment ago that your men never take matters into their own hands. Your men follow orders or people die. So Santiago shouldn’t have been in any danger at all, should he have, Colonel?

Jessup: You snotty, little bastard.

So why the two orders, Governor?

Tushar Nene

Staff Writer

@tusharnene

Over the last couple of years there’s been a lot of focus on legislation concerning internet privacy and regulation. SOPA came and went. CISPA was effectively (so we thought at the time) dead but is rearing its ugly head once again. ACTA was killed last summer. But all of those can have thousands of words dedicated to just them on their own. Today we’re going to be talking about the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, affectionately known as CFAA for short.

Over the last couple of years there’s been a lot of focus on legislation concerning internet privacy and regulation. SOPA came and went. CISPA was effectively (so we thought at the time) dead but is rearing its ugly head once again. ACTA was killed last summer. But all of those can have thousands of words dedicated to just them on their own. Today we’re going to be talking about the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, affectionately known as CFAA for short.

The CFAA

The goal of the CFAA (when it was born from from the twisting nether ironically in 1984) was to reduce unauthorized access to computer systems for government and financial institutions. OK, fair enough. But the number of amendments that were attached to it over the next couple of decades changed its tone. In 1994 Congress turned it into a weapon for private litigants suing for civil damages, giving private business a means to sue employees for alleged information theft. 2001’s Patriot Act amended it to allow searching records from a user’s ISP. Each amendment suffers the same kind of vague, broad and overreaching language that we’ve grown to know and cringe at just like other proposed internet regulation has. A broad interpretation of the CFAA justified criminal charges for employees that violated a company’s acceptable use policy or violating an internet terms of use policy. Criminalized. Thankfully that last one was changed again in 2011, to bring the focus of the law back to what it originally was – combating unauthorized access to information. But it still had the power to destroy.

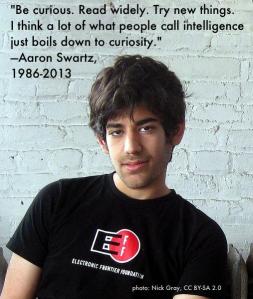

The case of Aaron Swartz

The most prominent case illustrating this was that of Aaron Swartz, a bright digital innovator and activist that helped develop RSS content syndication and the creation of the Creative Commons licenses. He also was the founder of the online group Demand Progress, an activist group that was well known for their digital campaign against SOPA. The case was around his access to information from JSTOR, a not-for-profit repository of scholarly and academic journals created in 1995 to help academic libraries and publishers provide access to their works without taking up physical shelf space. Users that have JSTOR accounts through an academic institution have free and unfettered access to this repository. Swartz’s position as a research fellow at Harvard University granted him access to the JSTOR system. According to the Department of Justice however, Swartz did so from a “protected computer” on MIT’s campus, with the intention of stealing documents and sharing them sharing them over numerous file-sharing sites, leaving him open to prosecution with the full strength of the CFAA. If he was convicted of the charges (wire fraud and computer fraud as violations of the CFAA) he could have faced up to 35 years in prison and fines up to $1 million. Sadly, Swartz hanged himself in his Brooklyn apartment this past January.

The most prominent case illustrating this was that of Aaron Swartz, a bright digital innovator and activist that helped develop RSS content syndication and the creation of the Creative Commons licenses. He also was the founder of the online group Demand Progress, an activist group that was well known for their digital campaign against SOPA. The case was around his access to information from JSTOR, a not-for-profit repository of scholarly and academic journals created in 1995 to help academic libraries and publishers provide access to their works without taking up physical shelf space. Users that have JSTOR accounts through an academic institution have free and unfettered access to this repository. Swartz’s position as a research fellow at Harvard University granted him access to the JSTOR system. According to the Department of Justice however, Swartz did so from a “protected computer” on MIT’s campus, with the intention of stealing documents and sharing them sharing them over numerous file-sharing sites, leaving him open to prosecution with the full strength of the CFAA. If he was convicted of the charges (wire fraud and computer fraud as violations of the CFAA) he could have faced up to 35 years in prison and fines up to $1 million. Sadly, Swartz hanged himself in his Brooklyn apartment this past January.

There are tons more details to this case I’m glossing over, but you can read more about the whole thing at the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Present Power and Proposed Changes

That’s the power the CFAA has as it stands. In the wake of Aaron Swartz’s death, many politicians, including SOPA critics Rep. Darrell Issa (R-CA) and Rep. Jared Polis (D-CO), raised questions about how the government handled the case, and Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-CA) proposed to reform the CFAA with Aaron’s Law, to prevent what happened to Swartz to happen to other computer users. This reform is extremely important in the internet age, because according to the bill, you don’t have to be a hacker or know anything about hacking to be charged for unauthorized access. In the words of Orin Kerr, a law professor at George Washington University,

“Breaching an agreement or ignoring your boss might be bad. But should it be a federal crime just because it involves a computer? If interpreted this way, the law gives computer owners the power to criminalize any computer use they don’t like. Imagine the Republican Party setting up a public website and announcing that no Democrats can visit. Every Democrat who checked out the site could be a criminal for exceeding authorized access.”

So reforming this bill would be in the best interests of the internet and all American internet users, right? So why are new proposed amendments aimed at dealing more damage instead of fixing what’s broken? Looking at the new draft (which you can see here) just talking about violating the CFAA will carry the same punishment as actually completing the act itself, by adding the short phrase “for the completed offense.” There’s also language that links CFAA violations to racketeering, putting every violator on the same level as a member of an criminal organization. In addition to violating website’s fine print being a criminal act, the proposed changes expand the scope of civil seizure and forfeiture by the federal government. And one of the most frightening additions is a section on “exceeding authorized use,” meaning that if I want to access information I legally have access for an “impermissible purpose” then I’m punishable. I’m not saying that’s a common thing, but it could be another arrow in a prosecutor’s quiver.

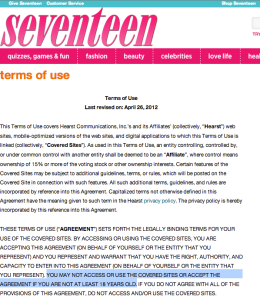

Terms of Use Violations and… Seventeen Magazine?

Yes, that’s right, Seventeen Magazine. Upon hearing of the new proposed earlier this month, they immediately changed a very specific part of their terms of service. Their terms of service used to read that you had to be at least 18 years of age to access the website, meaning that if you couldn’t access Seventeen if you were… actually 17. They have a readership of 4.5 million teenage readers, whose average age is 16 and a half. As of April 3rd, that language has been removed. Otherwise, under the new proposed CFAA changes, over 4 million teenagers could have been charged with computer crimes just for visiting the site, violating the user site agreement fine print. Hearst Magazines realized that this was ridiculous, and thankfully chose not to turn an army of teenagers into felons.

Yes, that’s right, Seventeen Magazine. Upon hearing of the new proposed earlier this month, they immediately changed a very specific part of their terms of service. Their terms of service used to read that you had to be at least 18 years of age to access the website, meaning that if you couldn’t access Seventeen if you were… actually 17. They have a readership of 4.5 million teenage readers, whose average age is 16 and a half. As of April 3rd, that language has been removed. Otherwise, under the new proposed CFAA changes, over 4 million teenagers could have been charged with computer crimes just for visiting the site, violating the user site agreement fine print. Hearst Magazines realized that this was ridiculous, and thankfully chose not to turn an army of teenagers into felons.

It’s important that people know what’s going on with this kind of legislation – any laws that affect computer use affect all of us, and we as citizens should actively be making sure that our own day-to-day activity can’t be potentially weaponized against us. If you want to contact your representatives about the CFAA (or anything else for that matter) the EFF has a lookup tool you can use to know where to send your comments and letters.

This is far from the first and far from the last when it comes to skewed computer law. Outside of recruiting more geeks in Congress, our voice is all we have.

Tushar Nene

Staff Writer

@tusharnene

Do all of you know what I love most in this world? Good television and…….Fried chicken, it’s pretty great, and not at all the point of the article. But I was eating some while I was writing this and I felt the need to share. But fried chicken is not the point of this article, it is just the greasy glue that holds this together and while I would love to talk more about how awesome fried chicken is, I am fairly certain that is not why you are here.

The point of this article and the reason for oodles of excitement recently was the release of House of Cards on the first of this month. For those of you who don’t know, House of Cards is an American adaptation of a British mini-series, now I know what you are thinking but hold your judgement for a moment while I blow your minds, or at least open your minds a little bit about this piece of amazing television. House of Cards is Netflix’s foray into original programming…Wait…what is that you say? Original programming? Netflix? Oh say it ain’t so! (Ain’t, ain’t a word and you shouldn’t use it unless you are making a poor grammatical joke.)

The people who want to make good TV are slowly abandoning the networks for cable and the internet. Shows, like Game of Thrones, Battleground, and House of Cards are great examples of genre television that has slowly been going out of style on major networks. But content providers like Netflix are more than happy to make things that people want to see.

House of Cards is, at it’s most base value a story of ambition, greed, vengeance, and the lust for power. All of those traits can be found in it’s main character Frank Underwood, House Majority Whip portrayed in the most vicious and staggering fashion by Kevin Spacey. Driven by ambition and undone by the incompetence of others, the Underwoods begin the series awash in the intoxicating celebration of a presidential campaign unaware of the events that will transpire in the beginning parts of the act.

Lady McB?!

It is hard to say what this show would be without Kevin Spacey, but the same can be said for Robin Wright, who portrays his wife Claire, She is the Lady to his Macbeth. A woman of ambition and cunning, who understands the game as well as her spouse. Robin Wright portrays Claire, with a softness that disguises steel. Powerful and provocative she is one of the main reasons I was drawn to House of Cards.

I think the part I love most about this show is while it borrows from the British version, it makes the concept it’s own and it runs with it. Spacey is Macbeth, Richard III, and any other Shakespearean character that longs after power. He will do anything to acquire it and the path he takes to get there is one I am willing to follow. This show is something everyone should be watching and by the time we make it back around to Emmy season, I wouldn’t be surprised if Spacey and Wright are looking and a brand shiny new pair of statues.

Have you caught an episode yet? What did you think? Let me know in the comments below or on twitter!

Samuel Smith

Staff Writer

@insomniawalking

I love technology and the explosion of mobile tech in the last decade – it’s allowed users in the United States and around the world to completely change and enhance the way we communicate and run our day to day lives. Availability of information empowering the American consumer. Activism. Giving users a voice. And as much good as it’s brought, it’s also brought its own set of problems. With every new service made available to the American public comes an additional way to screw the American public – be it another veiled method of control or a straight up financial jack. Tech rivals make backroom deals while suing each other to take customer favorites off the market. Some folks still pay a 7,000% upcharge for something as simple as sending or receiving a text message. And now, while your mobile bills can top $150 a month based on your device and expanding data usage, the industry is still a cash-devouring beast that cannot be fed. The end result? American consumers paying more money for less control over devices they own, which on their own can cost upwards of $600 if not subsidized with a contract renewal or some other pricing scheme.

I love technology and the explosion of mobile tech in the last decade – it’s allowed users in the United States and around the world to completely change and enhance the way we communicate and run our day to day lives. Availability of information empowering the American consumer. Activism. Giving users a voice. And as much good as it’s brought, it’s also brought its own set of problems. With every new service made available to the American public comes an additional way to screw the American public – be it another veiled method of control or a straight up financial jack. Tech rivals make backroom deals while suing each other to take customer favorites off the market. Some folks still pay a 7,000% upcharge for something as simple as sending or receiving a text message. And now, while your mobile bills can top $150 a month based on your device and expanding data usage, the industry is still a cash-devouring beast that cannot be fed. The end result? American consumers paying more money for less control over devices they own, which on their own can cost upwards of $600 if not subsidized with a contract renewal or some other pricing scheme.

If you know me on Facebook or Twitter you would have seen me ranting this past Friday about a new law that went into effect this weekend affecting mobile tech, complete with pleas to the big three carriers Verizon Wireless, AT&T and T-Mobile. The reason was some new legal developments that went into effect this past weekend. According to the Librarian of Congress and the DMCA (Digital Millenium Copyright Act), unlocking your phone or mobile device is now against the law.

Yes, you read that correctly. From now forward, if you unlock your phone, you have committed a Federal crime. And I’ll repeat myself, because I feel this bears repeating: If you decide to unlock your phone – the one that you own, which you spent hundreds of dollars and hours of research to purchase, under the DMCA you are a criminal and punishable by the law.

I’m going to try and split this up because I’m throwing a lot of information at you. For those of you that don’t want to read through this entire thing and get right to the brass tacks, skip ahead to the “How this can affect you” section.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act and Exemptions

The DMCA was established in 1998 to criminalize the creation and distribution of any technology that could bypass digital rights management systems implemented in various forms of media, as well as the people who use or host those technologies. Stuff like software key generators, hardware hacks and modded game consoles fall under this. The way it’s set up, the power to name exemptions to DMCA enforcement rests with one person, the Librarian of Congress. These exemptions have a shelf life of three years, at which time the group requesting the exemption must re-lobby and re-convince Congress to keep that exemption in place. It’s that arbitrary system that is causing this headache now. Back in October, the recent list of exemptions was released, and included an extremely convoluted list of what’s exempt and what’s not involving your mobile tech. Now the way it stands for the next three years:

On cell phones purchased in January 2013 or after, jailbreaking is acceptable, but unlocking is not. That OK for jailbreaking, however, does not extend to your tablet. So if you want to do the same to your iPad, you’re out of luck. These rules come with some very specific language – saying that the phone has to be “originally acquired from the operator of a wireless telecommunications network or retailer no later than ninety days after the effective date of this exemption.” What this means is that on your current phones, purchased in December 2012 or earlier, can still be unlocked without penalty. But if you want to unlock something you bought this month or later, you can do no such thing without your carrier’s permission. The Librarian set this up in October, but was nice enough to give people a 90 day grace period until January 2013 so people could buy phones they planned to unlock later. But that time’s over now, kids.

I just don’t see the authority here. What the hell does this have to do with piracy and copyright infringement? Kind of reaching, Mr. Librarian.

Jailbreaking vs Unlocking

While these two terms may sound like the same thing, they’re actually quite different. Jailbreaking a device means that it has the capability to download 3rd party apps not sold or released by the manufacturer. This phrase became popular with the iPhone, where users would jailbreak their devices to download apps not purchased from Apple’s App Store. Unlocking a device means that you remove the software that locks a device to a specific carrier. For example, if I wanted to use an AT&T device on Verizon Wireless, then that device would have to be unlocked to allow me to do so. So you can see how carriers would love keeping those locks down, so they can keep you right where you are. Phone carriers offer subsidies on contract renewals so they can make up that difference over a 1 year or two year contract (similar to a loss leader kind of sale). With data heavy customers, they make that back in about 2-4 months of a contract. Unlocking your phone and jumping ship, even after paying a huge termination fee, still loses them some profit. Not really money, but profit.

We’ve Played by Your Rules

Termination fees. Yeah. If the above described action happens, I owe my carrier up to $350 in the form of a termination fee. I can’t refute that, it’s in my contract that I agreed to. So there’s already a mechanism in place to protect the carrier from little ol’ me. Without Federal law. Just throwin’ that out there.

How this Affects Users

For a lot of people this probably isn’t going to be a big deal as far as how they use their devices because they don’t jailbreak or unlock them. But there’s an increasing number of people that do. Even if you don’t do anything like this with your devices though, it’s still something to pay attention to because this new set of exemptions affects us all in a number of ways. On a fundamental level, this move is a strike against digital freedom and sets exactly what degree we actually own the tech we think we do. If I buy a house I can paint the walls any color I want to. When I buy a car I’m not restricted to what kind of gasoline I can use. And when I buy a PC, there’s no rule that says that I can’t replace my OS. But now if I buy a cell phone, my actions with it are now somehow up to the Librarian of Congress.

And part of that is thanks to the 2010 court case Vernor v. Autodesk, where it was decided that we own our phones, just not the software that sits on it.

Financially is where the impact will be felt a little more heavily. With the legal inability to unlock your own phone, if you want an unlocked phone you’ll have to buy one unsubsidized at full price. For example last year when I bought my Droid Razr MAXX, I got it at a significantly discounted cost (i think it was $299) because I was renewing my Verizon Wireless contract at the time and reaped the benefit of VZW subsidizing my purchase. Now if I want to buy a phone of the same grade but have it unlocked, I would have to shell out somewhere in the neighborhood of $650 and up for that device. For those that were unaware, yes, that’s how much good smartphones cost on their own these days.

Travelers can also face some issues. Someone with an unlocked phone can take it global, and just switch SIM cards at each destination to be able to use their own device. This kind of convenience just became a lot more expensive.

Users can still buy phones that are already unlocked from their carriers, but it might cost them a pretty penny. Some devices, like the iPhone 5 and Google’s Nexus 4, come unlocked out of the box, which is OK under the new law, and under certain situations the carrier will unlock a device for you, but don’t expect them to just go along with it. Either way, the bottom line is that carriers win, and users lose.

So what are these consequences one would face should they choose to unlock their phone? The CTIA has been kind enough to outline them for us on their official blog. They, and subsequently the carriers, are the biggest beneficiaries of this whole mess:

“The penalties for unlocking a subsidized wireless phone without carrier consent can be severe. Civil penalties are based on the carrier’s actual damages and any additional profits of the violator, or a court can award statutory damages of not less than $200 or more than $2,500 per individual act. Criminal penalties are even more severe: any person convicted of violating section 1201 willfully and for purposes of commercial advantage or private financial gain (1) shall be fined not more than $500,000 or imprisoned for not more than 5 years, or both, for the first offense; and (2) shall be fined not more than $1,000,000 or imprisoned for not more than 10 years, or both, for any subsequent offense.”

This is of course by no means an exhaustive analysis of the situation – there’s a number of factors involved. There’s another part of this exemption list that involves DVD/blu-ray media and your mobile devices, and I’ll cover that in part II.

Tushar Nene

Staff Writer

@tusharnene

In the United States, we have a video and computer games rating system that makes sense. It’s managed by the ESRB, and from eC (early childhood) to AO (adults only) the range of ratings make it pretty easy to know what to expect. Thanks to this system, a majority of the time we can make an accurate pre-purchase assessment about whether or not the game is appropriate for the audience we’re buying for. As much as your 8 year old kid would love to play God of War, the M rating on it may make you think twice about letting him or her get their Greek godly gore on. Something rated E may be more the speed you’re looking for. And there’s a rating band for everything, broken down even further than MPAA ratings for movies: between eC and AO are E (everyone), E10 (everyone 10+), T (teen), and M (mature). Similar ratings systems exist in other parts of the world too. In Europe for example that’s PEGI (Pan European Game Association). And for the most part they work – just ask the FTC. But there’s some parts of the world where these systems are (well, were) kind of broken and in need of some repair. And the place in question today is Australia.

In the United States, we have a video and computer games rating system that makes sense. It’s managed by the ESRB, and from eC (early childhood) to AO (adults only) the range of ratings make it pretty easy to know what to expect. Thanks to this system, a majority of the time we can make an accurate pre-purchase assessment about whether or not the game is appropriate for the audience we’re buying for. As much as your 8 year old kid would love to play God of War, the M rating on it may make you think twice about letting him or her get their Greek godly gore on. Something rated E may be more the speed you’re looking for. And there’s a rating band for everything, broken down even further than MPAA ratings for movies: between eC and AO are E (everyone), E10 (everyone 10+), T (teen), and M (mature). Similar ratings systems exist in other parts of the world too. In Europe for example that’s PEGI (Pan European Game Association). And for the most part they work – just ask the FTC. But there’s some parts of the world where these systems are (well, were) kind of broken and in need of some repair. And the place in question today is Australia.

In Australia, game ratings are determined by the Australian Government’s Classification Board, but their ratings differed a little bit until recently from ESRB and PEGI style classifications. While ESRB and PEGI have ratings for games meant for adult audiences, Australia didn’t, only going up to an MA15+ at the maximum. So some games targeting adults that were released to the rest of the world never made it to the land down under. Mortal Kombat titles for example were banned there. Other games, like Silent Hill: Homecoming were modified by publishers so the Australian editions of the game conformed to MA15+. It became a real problem down there – as systems become more advanced thy’re more capable of showing realistic scenes including violence, which meant that Australian gamers had even that much less of a choice going to pick up some games.

In Australia, game ratings are determined by the Australian Government’s Classification Board, but their ratings differed a little bit until recently from ESRB and PEGI style classifications. While ESRB and PEGI have ratings for games meant for adult audiences, Australia didn’t, only going up to an MA15+ at the maximum. So some games targeting adults that were released to the rest of the world never made it to the land down under. Mortal Kombat titles for example were banned there. Other games, like Silent Hill: Homecoming were modified by publishers so the Australian editions of the game conformed to MA15+. It became a real problem down there – as systems become more advanced thy’re more capable of showing realistic scenes including violence, which meant that Australian gamers had even that much less of a choice going to pick up some games.

Over the last couple of years there has been a lot of debate in the Australian government about whether or not the Classification Board should create new ratings to allow for adult-themed games, or as they call them, games with “high-impact” themes. And after a lot of back and forth they finally decided that it would be a good idea. Starting this year, two new classifications were effective: R18+ and X18+, both illegal to sell to persons under 18 years of age.

Well today Australian gamers can rejoice, as Lesley O’Brien, Director of the Classification Board put out a media release announcing that the R18+ classification would finally be in effect, and that the first game to carry the rating is going to be Ninja Gaiden 3: Razor’s Edge on Nintendo’s Wii U. Prior to 2013, Nintendo would have been refused classification for the game, prohibiting sale of the game in the country.

Well today Australian gamers can rejoice, as Lesley O’Brien, Director of the Classification Board put out a media release announcing that the R18+ classification would finally be in effect, and that the first game to carry the rating is going to be Ninja Gaiden 3: Razor’s Edge on Nintendo’s Wii U. Prior to 2013, Nintendo would have been refused classification for the game, prohibiting sale of the game in the country.

According to the release, “The Classification Board classified the game R18+ (Restricted) with consumer advice of ‘High impact bloody violence’.” Further, “Ninja Gaiden 3: Razor’s Edge contains violence that is high in impact because of its frequency, high definition graphics, and emphasis on blood effects.” Now the game will have an official R18+ rating, matching the ESRB’s M and PEGI’s 18+ ratings in the United States and Europe, and Ryu Hyabusa’s ninja antics can be executed across the outback.

I’m a firm proponent of video game ratings and do think that they provide folks (especially parents) with guidance as to what kind of content is inside. Everybody should familiarize themselves so they know the score a little better, and I will more than happily guide you to those resources: sites for the ESRB, PEGI, and the Australian Classification Board

Thanks Game Politics for the heads up!

Tushar Nene

Staff Writer

@tusharnene